In the mid-'90s, the Mac LC III capacitors were installed backwards due to faulty silkscreen printing on the board. The capacitor was not upside-down visually or orientation-wise but in voltage. You'll notice if you try to replace it and start to smell ozone.

It seems unlikely that Apple will issue a factory recall for the LC III—or the related LC III+, or Performa models 450, 460, 466, or 467 with the same board design.

The "pizza box" models, sold from 1993–1996, came with a standard 90-day warranty and most probably ran without issue, although there were rumours that, like many Macs, they had a fire feature. The problem was when people tried to fix these boards and replace the capacitors (re-capping), they ran into trouble.

According to Ars Technica, Doug Brown first spotted the issue in a 2013 forum discussion and has seen it pop up elsewhere. Now, having "bought a Performa 450 complete with its original leaky capacitors," he can double-check Apple's board layout 30 years later and detail it all in a blog.

He confirms what many multimeter-wielding types long suspected: Apple put the plus where the minus should be.

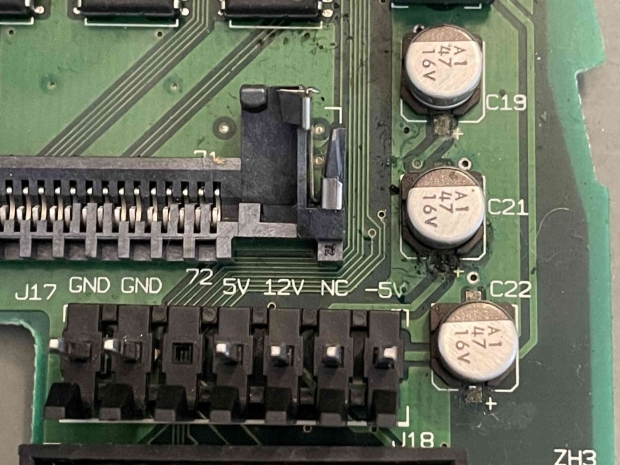

In the corner of the LC III board, near the power supply connector, there are three capacitors nearby, C19, C21, and C22. Each is boxed in with white silkscreen markings to guide the factory assemblers and future repairs. Each capacitor sits on one of the "rails" (DC power from the supply).

While C19 and C21 properly take on +5V and +12V lines from the power supply connector, the bottom C22 capacitor takes a -5V rail into its positive terminal. This capacitor (an SMD electrolytic) is not supposed to take negative voltage.

Brown notes that the predecessor Mac LC and LC II had the correct connections, as did the LC 475, which uses the same power supply scheme. This makes him "confident that Apple made a boo-boo on the LC III" or "basically the hardware equivalent of a copy/paste error when you're writing code."

What is strange is why no one seemed to notice this problem. It appears that the rail was only used for a serial port or certain expansion card needs, so a capacitor failure or out-of-spec power output may not have been noticed. The other bit is that the original capacitor was rated for 16V, so even with -5V across it, it might not have failed, at least while it was relatively fresh. And it would not have failed in quite so spectacular a fashion as to generate stories and myths.

This raises questions about whether Apple knew about this but decided against acting on it and correctly hoping that no one noticed.

Brown hopes anyone else re-capping one of these devices will put up a bright, reflective warning sign urging them to ignore Apple's markings and install C22 correctly.

He said he heard from another hobbyist that the reverse voltage "would explain why the replacement cap" they installed "blew up." Some restoration types, like Retro Viator, noticed and fixed the problem before the detonation.

Modern rehabbers use tantalum capacitors to replace the fluid-filled kind that probably damaged the board they're working on. Brown wrote to me that tantalum tends to react more violently to too much or reverse voltage.