Earlier this year Samsung launched the first commercially available big.LITTLE ARM SoC and unleashed its marketing machine, hyping the benefits of ARM’s big.LITTLE configuration and octa-cores in general. Qualcomm wouldn’t stand for it. Qualcomm’s outspoken CMO Anand Chandrasekher took a few less than diplomatic jabs at Samsung, saying octa-cores are “dumb” and that Qualcomm has no intention of building them, since its engineers “don’t do dumb things”.

From a purely technical perspective Chandrasekher was right and most technologists agreed with him. Qualcomm and Apple have made it abundantly clear that optimized custom cores can easily beat the brute force approach of smaller chip designers who use off-the-shelf ARM tech. However, there is a very good reason some companies are still betting on the “more is better” approach and it all comes down to money rather than silicon.

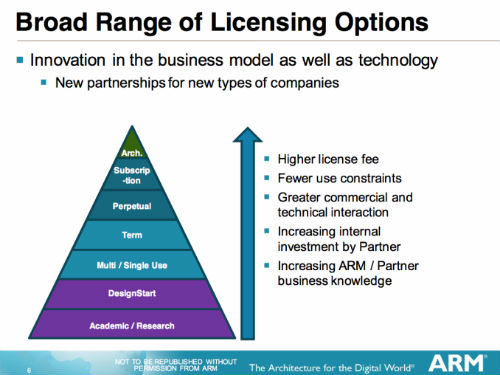

Designing custom cores is simply not an option for smaller outfits. They lack the resources and know-how to pull it off, so custom cores are reserved for big players, at the top of ARM’s licensing pyramid. On the face of it, this doesn’t leave smaller chipmakers that many options – they have to use what they’ve got, and they’ve got IP for reference ARM cores which they can’t play around with. However, operating under such constraints is forcing them to look for alternative ways of coming up with competitive designs.

One of the ways of getting around these limitations was demonstrated by MediaTek, in the form of their new Cortex A7-based octa-core, the MT6592. Although it’s an octa-core, it is practically a mid range chip, but in some benchmarks like Antutu it comes close to Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 600, but MediaTek’s chip has a much less potent GPU and since it’s an octa-core its real world performance won’t be as good as the benchmarks would have us believe, as most apps can’t put the additional cores to good use.

So why does it make perfect sense then? Well, ARM has a peculiar and complicated IP licensing model. In case you’re interested in the finer points of ARM’s business model and how it could apply to cheap octa-cores, you can check out this extensive report on Anandtech.

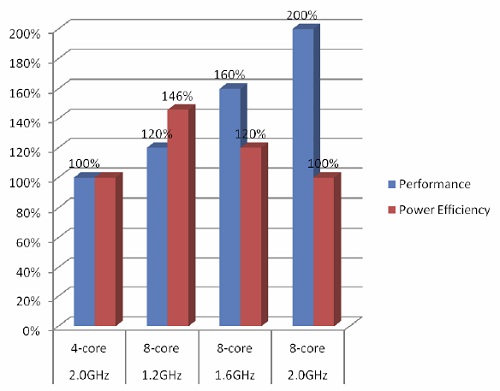

Since the big players can buy architecture licenses and play around with custom chips, they don’t necessarily have to add more cores to boost performance. This is Apple’s and Qualcomm’s turf, Samsung is also expected to roll out custom chips next year, although this is still not official. Smaller players aren’t in the architecture game, but they can still compete by building competitive mid-range parts. Since they can’t differentiate their products with fancy custom cores and GPUs, they can do what MediaTek is doing – stick plenty of cheap cores onto a single die and pray that the market will like the idea. Since MediaTek already has more than 20 design wins for the MT6592, it seems to be off to a good start. And here's what MediaTek claims when it comes to efficiency.

The Cortex A7 is tiny, it’s one fifth the size of an A15, which makes it an interesting choice to get more performance on a budget, on a relatively small die.

“When you consider that an A15 is five times the area and power of the A7, but only three times the throughput, it also becomes an attractive option on a die cost basis,” research firm Future Horizons told us.

What’s more, IP royalties for multiple A7 cores don’t cost nearly as much as A15s per core or per chip - there’s no need for an upfront A15 license fee, either. Using a familiar core also saves on design time.

In addition to MediaTek’s octa-core, which is the first and only A7 octa-core so far, there are a number of quad-core A7/A5 designs and most of them end up in cheap tablets and phones. They’re not nearly as powerful as a quad A9, but they are also a lot more efficient and don’t cost as much. In fact, tiny quad-core A7 SoCs are the weapon of choice for white-box tablet makers and since the market for $99 tablets is booming, this bodes well for Rockchip, Allwinner and MediaTek. For example, MediaTek is estimated to have a 50 percent market share in China and this year it should ship 200 million SoCs. Combined shipments of phones, tablets and PCs are expected to hit 2.3 billion units this year, smartphone shipments could hit the 1 billion mark soon and it’s clear that there’s a huge market for cheap mobile chips.

However, octa-core A7 chips are hardly a serious trend at this point and it’s unlikely that they will take off in all markets. The A7 simply lacks the power to be a viable long-term option, especially in demanding apps that don’t handle multicores all that well, i.e. games. To squeeze more performance out of octa-cores, developers would need to reconfigure their code to tap all the potential, but for that to happen octa-cores have to become relevant and thus justify the expense of extra coding. It’s a vicious circle and we’re not sure many developers will be willing to waste resources on such tweaks anytime soon.

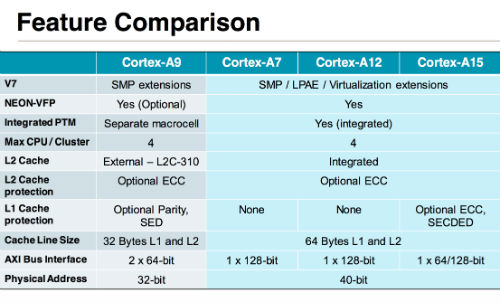

This is where it gets interesting, as MediaTek and Rockchip have already teased their first A12 quads. They should ship in early 2014. The A12 is about 40 percent faster than the venerable A9 it was designed to replace. In terms of performance, it’s close to Qualcomm’s first-gen Krait, yet it has a few interesting features, such as big.LITTLE support. On paper, it looks like a good choice for an octa-core, since it won’t be hampered by lacklustre single thread performance. Analysts agree that an octa-core A12 is one of the better choices in architecting such SoCs and if companies start announcing them, developers may have to start thinking about tweaking code for octa-cores, especially in Asian markets.

Then there’s also the possibility of using A12 cores alongside A7 or A15 cores in a big.LITTLE implementation, but although it’s technically possible such a configuration wouldn’t make as much sense as an A7/A15 combo.

We didn’t forget about 64-bit ARMv8 cores, either. However, the A53 is a small core and in terms of performance it should end up well behind the A12. The A57 could be great for server parts, but it doesn’t make too much sense for consumer devices, as it won’t end up much faster than the A15 and 64-bit support is still not very relevant in the consumer space. Add to that the higher licensing fees for A50-series products and ARMv8, along with more R&D and 64-bit overhead, the need to use costlier nodes and the new 64-bit parts start to lose their appeal, fast.

This means A7, A12 and A15 products will end up with a much longer shelf life than many people expect. It could also pave the way to more strange designs like MediaTek’s octa-core, or affordable, LTE-enabled big.LITTLE chips designed specifically for mid-range devices, a far cry from Samsung’s big ~$28 Exynos 5 Octa.